Drops: What’s in a name

Choosing a name, and more importantly… a bundle identifier?

It’s a common joke that naming things is one of the harder parts of computer science. There’s some truth to it too, but I don’t think all names are equally difficult. For example, a name that can easily be changed doesn’t give me a lot of pause, and this fortunately covers most of the type, property, and method names in a project. It’s always great to choose good names upfront if possible, but sometimes things change, and that’s what refactoring is for. Similarly, names that exist within some sufficiently narrow scope (like a private repository) really only need to make sense to their author. It’s the names that can’t be changed that I worry about.

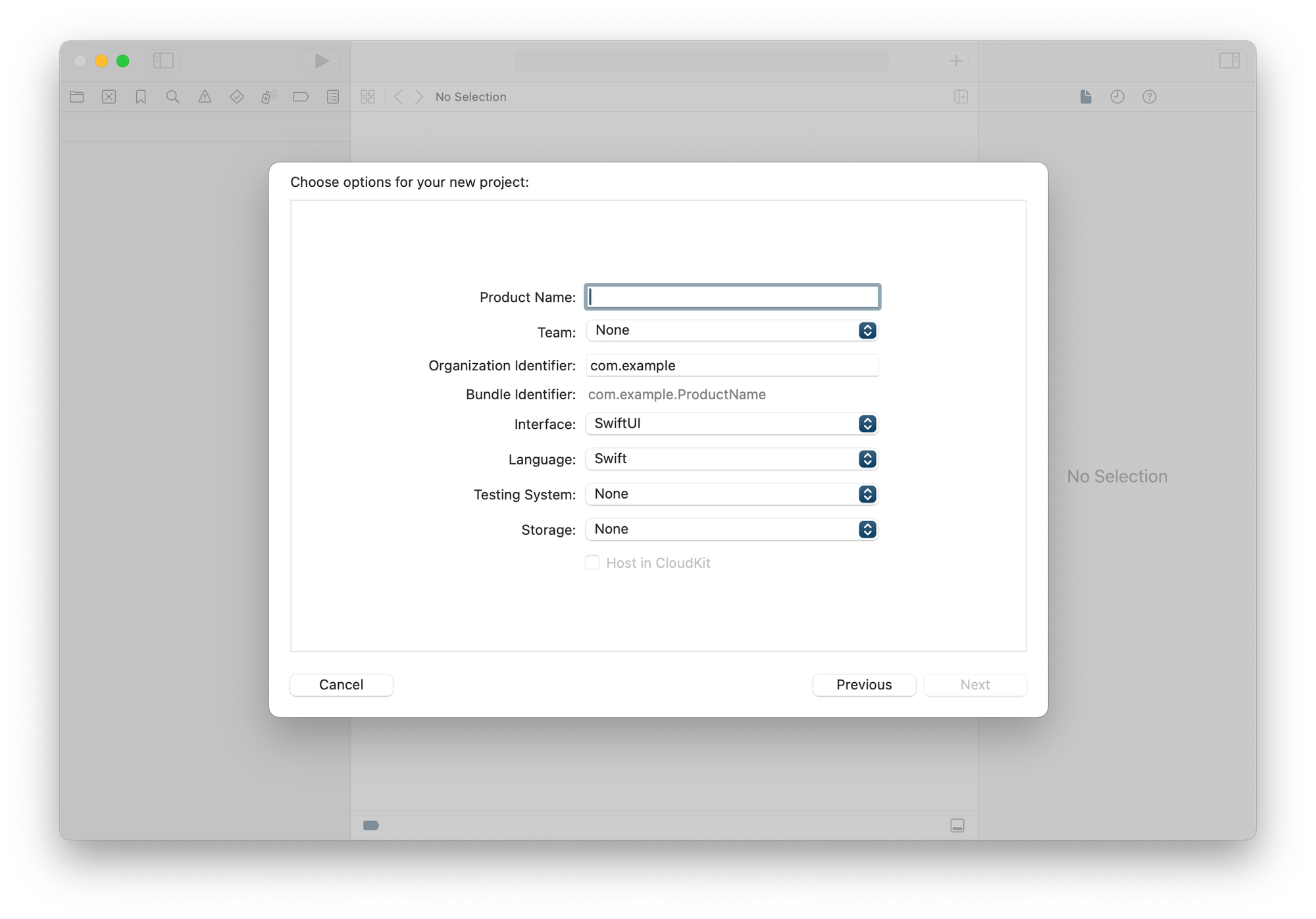

Xcode helpfully illustrates this duality by asking for both a product name and a bundle identifier as part of its new project form. While it’s tempting to think that the product name matters more here (that’s an app’s brand after all) it’s really the easier of the two to actually change. That’s because, unlike a marketing name, an app’s bundle identifier becomes permanent once submitted to the App Store. In some cases it may be possible to delete and remake the App Store Connect record, such as while beta testing, but once an app is actually published don’t expect an easy time updating it. Bundle identifiers must survive through rebrands, updates, and even IP sales (which is why Tweetie Twitter X’s iOS app still answers to com.atebits.Tweetie2). By convention, these identifiers also include a domain name, which ties them to yet another difficult-to-change name. So as far as names go, I think bundle identifiers deserve more thought than they always get.

An app’s bundle identifier (specifically) also goes into more than just one product. Modern apps are frequently comprised of embedded bundles, supporting features like widgets, app intents, or other extensions; which are required to take their app’s bundle identifier as a prefix of their own. Even some non-embedded bundles have this relationship, as seen in app clips or watchOS apps.

I think Apple Watch apps are particularly interesting because of how their packaging has evolved. These started as a watchOS app embedded within an iOS app, and within that watchOS app bundle was another embedded watchOS app extension. The bundle identifiers of all these pieces reflected this, being patterned as com.example.ios-app for the iOS app, com.example.ios-app.watchkitapp for the actual watchOS app, and com.example.ios-app.watchkitextension for its extension. This nesting made sense, since watchOS apps were literally installed by copying them from their containing iOS app on a paired phone. Over time the architecture changed, first by moving and running the extension bundle to the Watch, and then by merging it into the watchOS app as well (which is how apps for all other platforms work). In watchOS 6 this culminated in “independent apps”, which could be installed without a paired phone, and were downloaded directly from the App Store. Despite these changes, Watch apps still reflect their heritage, with the current Xcode templates still using a *.watchkitapp bundle suffix, even when created without an iOS app. There should be an asterisk there though, as these projects still include a stub iOS app target, with a valid bundle identifier, just to place them inside of when uploading to the App Store.

This identifier prefixing goes deeper than mere convention. It’s actually required by Xcode, which will fail to embed bundles that do not follow the rules (this link mentions watchOS apps, but it’s also true for other things). I find it interesting that this is a hard requirement, unlike the (highly recommended, but not actually enforced) convention of reverse DNS notation. Being able to infer relationships between bundles is surely nice for debugging, and for better or worse it also means that an extension bundle can’t ever move between different apps or have a bundle identifier collision (on iOS, where uniqueness is better enforced), but if it’s also a security mechanism then it would appear incomplete. This is because some APIs must also use additional methods to define these associations, like the com.apple.developer.parent-application-identifiers entitlement for app clips, or WKCompanionAppBundleIdentifier for watchOS apps.

The final bundle identifier consideration I want to bring up is Universal Purchase, which is a feature that allows apps across separate platforms to be aggregated under a single App Store product. There are some additional requirements for Universal Purchase, but one of the big ones is that these separate apps must share a common bundle identifier, despite them being built and submitted to the App Store separately. This requirement walked back a common practice of giving iOS and iPadOS apps a unique (often *Mobile suffixed) identifier from their Mac counterparts, something started by Apple’s own apps. It also caused some problems for early adopters of Mac Catalyst, where Apple initially required a new bundle identifier for Catalyst apps, making them not directly compatible with Universal Purchase. For the same reason, supporting iPad and iPhone using separate apps has caused problems for developers, as these would need separate bundle identifiers and App Store products, which can neither be merged or split. It is still possible to create platform-specific App Store records while sharing a bundle identifier, then later decide to combine them into a Universal Purchase product. This will still require deleting all but one platform’s record, losing reviews and the ability to update existing users’ apps, but it feels like yet another reason to not have more bundle identifiers than necessary.

What does all this mean for me? Fortunately Drops’ packing should be relatively simple. I think it could benefit from a watchOS app (some day), but there’s a requirement that watchOS apps always need a unique bundle identifier, and how to derive it from an iOS app. I don’t have specific plans to support any other platforms, including an iPad specific interface, although I would personally opt to reuse a single bundle identifier across platforms regardless. My biggest issue was simply whether I wanted to use my personal website for Drops or buy it its own domain. In the past I’ve always used com.axiixc.* for my apps, but wasn’t as sure about this one. Buying a new domain comes with its own issues though, like choosing on a marketing name upfront. I’m now fairly certain of my branding, but I did start off with com.axiixc.proto.Drops for the first few months. Even that “proto” speaks to some (probably unnecessary) uncertainty, but I’ve had issues in the past where Apple Developer Connect and other tools make it difficult to delete records, so I always try to reserve any “good” names for when I’m more confident.

To round things out, I also want to talk briefly about the Product Name that Xcode asks for. Despite appearing as a single text field, Xcode actually uses this for three things in a new project:

- The first is as the name for a new target. Targets are unrelated to apps or bundles, and are instead part of how Xcode organizes projects. Targets can be named anything, and can be changed at any time. In a standard Xcode project setup, targets are referenced within the project file by internal identifiers. However, with custom script phases or other build tools, these targets’ names may be used as command line arguments instead, so there a small but usually localized risk of breaking something.

- Product name also affects the name of the product built from this new target, as one would expect. While you can change this name after publishing an app, it’s usually not too important to update it. End users are unlikely to ever see an app bundle on iOS, because the filesystem isn’t accessible in the same way as on macOS. Changing a product name will also require clearing the build directory, and could cause other issues if the product path was used as a script phase dependency or similar. Xcode also does not use the supplied product name directly, instead substituting it from the target name. This can bee seen as

PRODUCT_NAME = "$(TARGET_NAME)";in a project’sproject.pbxproj. This means that renaming a target may also rename the app’s bundle. - Finally, is the app’s

CFBundleName, which is the name iOS displays to users. Be aware that this too is a substitution in the default Xcode template, this time of the product’s$(PRODUCT_NAME)(which is itself a substation of the target name). Like other Info.plist values, it can be localized, in which case the app’s name will come from the respective strings file instead. (I should also mentionCFBundleDisplayName, which on iOS appears to simply take precedent overCFBundleName. This differs from macOS, where the two keys do have different functions.)

I hope that these examples have some helpful things to think about when starting a new project. Bundle identifiers’ importance can be easy to overlook as just boilerplate, but they’re important to many parts of the operating system. I wouldn't worry too much at the very start, but it’s good to think about where an app might go before committing to it in App Store Connect. Some things really are easier to get right upfront. I would also personally appreciate if TestFlight could operate more independently from the App Store, offering some way to start testing apps without needing to go through the overhead of App Store Connect. I probably wasted a week of time just researching my choices and buying a domain name before I felt comfortable submitting to TestFlight, which was a real distraction when all I wanted were a few more eyes on my work. Now that I’ve bought a domain to go with it, hopefully remain happy with my choices.